‹ Heritage

19th Century Tatting

Lace was in great demand in the 19th century. Everyone wanted some, but the classic laces were extremely expensive, out of the reach of most people. This encouraged creativity, which was helped too by the newly available tougher mercerized threads produced from about 1840. Inventive needleworkers found ways of making lace that were relatively inexpensive and also much quicker to produce than the traditional forms. One of these was tatting.

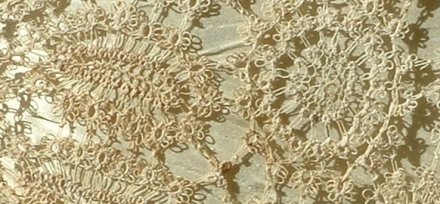

The first tatting consisted of rings only - usually worked in a length of slightly spaced rings. The rings would be arranged and laboriously stitched together in motifs as you see below. Often needle-lace fillings were worked in too. The square doily pictured below (11.5" or 29cm square) was tatted in this way, which probably dates it to the 1840's. (Or it could be later, but done by an old-fashioned tatter who hadn't caught up with the latest methods.)

When it came to joining motifs, a thread was run through 2 picots and tied in a knot and the ends cut. Here you can see the knots:

The early tatting, using only rings and picots, seems primitive to us now. Yet those early tatters managed to produce large and elaborate pieces, such as the cover for this beautiful silk-lined parasol:

As can be seen from the detail (below), the way this was done was by producing lots of small motifs, made from strings of rings shaped into circles or ovals with needle lace, and then joined together patchwork-style with even smaller motifs and thread ties through picots to produce a lace fabric.

This parasol probably dates from the 1850s, when they became very fashionable and as much a status symbol as a protection from the sun. There is a pattern for a parasol cover in Mademoiselle Riego's book "The Lace Tatting Book" (1866) - see the list of Historical Tatting Books.

It is always hard to trace the history of domestic arts and crafts. So much was passed on from person to person by example and by word of mouth. But the 19th century saw an increasing number of publications on all kinds of subjects, including tatting. So it is that we know that tatting was around in 1843 because a booklet on the basics of tatting was published then.

The renowned Mademoiselle Eléanore Riego de la Branchardière (usually known simply as Mlle. Riego) published 11 booklets on tatting from 1850 onwards (see Georgia Seitz' Archive of Tatting Books in the Public Domain). In the these booklets we can see tatting develop before our eyes:

- 1850 - "The Tatting Book" by Mlle Riego recommended tatting, not with a shuttle, but with a fine netting needle which could pass through picots to join them. See her Preface for a description and her impatience with the old method.

- 1851 - "Tatting Made Easy" by "a Lady" included the crucial instructions on joining picots by hooking a loop of the shuttle thread through a picot. There would be no more tying picots together with knots after that! Unfortunately the Lady kept her anonymity, so we cannot give her due recognition.

- 1861 - "Tatted Edgings and Insertions" by Mlle Riego included a very clear diagram (page 4) showing how to join rings as we do today - only using a tatting pin rather than a hook. Netting needles were not mentioned after 1850.

- 1864 - "The Royal Tatting Book" by Mlle Riego has a pattern for an edging (page 18) with the first example of a proper chain, worked with two shuttles, and clear instructions.

So, from 1864, tatters knew the techniques that are essential today: how to make rings, chains and join picots.

Here are some tatting shuttles typical of those used in the 19th century:

The tortoise-shell shuttle above measures 3.3" (8 cm) in length. As with many old tatting shuttles, the ends have drifted apart. The bone shuttles measure 3.25" (8.5 cm) and 2.8" (6.5 cm) in length. They still have the closed ends which make tatting much easier.

Shuttles like these can still be bought quite cheaply on the internet or from antique fairs. It is lovely to have at least one, and feel a connection with Victorian tatters. Many more decorative shuttles were available too - see the list of Historical Tatting Books.

This fine handkerchief (9.5" or 24cm square) was made in the late 19th century, judging by a similar example in Rhoda Auld's book. It was hem-stitched by hand and edged in No. 100 thread- a simple ring and chain edging and then a ring-only "Hen and Chicks" edging:

We would love to add more examples of antique tatting, so if you have some, please do send us a photo or scan. Thank you Brenda for your contribution.

Please note: the text above is from an article © Sally Magill 2006. Others may use it free of charge, provided they acknowledge the copyright.